There’s a Houston community that holds national historical significance, even though many locals know little about it. Nestled between N. Shepherd Dr. to the left and I-45 to the right, with Tidwell Rd. to the north and the northern 610 loop to the south, lies one of the most historic communities not only in Texas, but in the nation. That community? Independence Heights.

Helping to shed light on this hidden gem is Tanya Debose, a fifth-generation descendant of the people who founded Independent Heights and executive director of the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council founded in 2005 to improve the quality of life for people in Independence Heights, particularly through historic preservation and revitalization activities.

DEFENDER: What’s the story behind Independence Heights’ founding?

DEBOSE: Around 1905, the A.A. Wright Land Company began buying up land and repatterned it as a neighborhood. Prior to that Independence Heights was really a lot of pasture land with cows and open prairie. The WLC began platting land out there. The thing unique about the WLC is they actually sold land to both whites and African Americans and they sold land to African Americans at a fair price. The wards were filling up. A lot of people were coming to Houston because of the jobs. So, Independence Heights presented this opportunity via the WLC around 1908, where you could literally own land and build the house you wanted. About 1915, 600 residents populated the city.

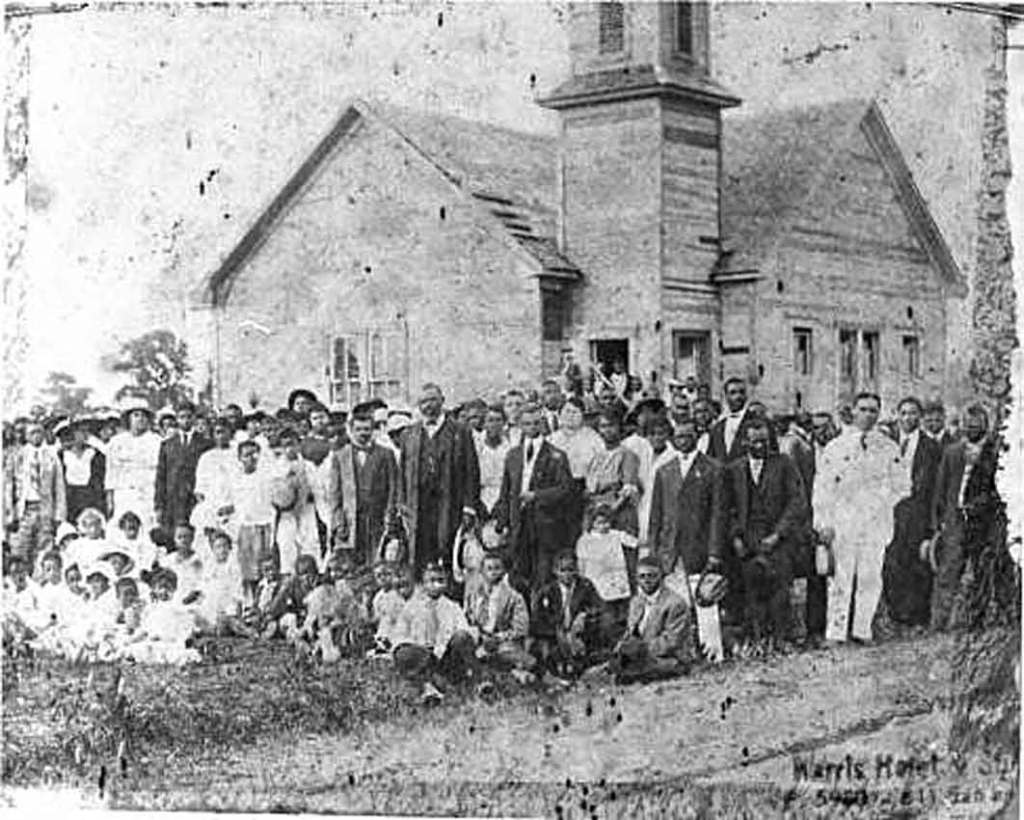

They built churches, had their own corner stores, and just about everything they needed right there in that town. At the same time, the city of Houston started getting amenities like indoor plumbing and paved streets, and the people of Independence Heights wanted those same opportunities. When they tried to work with the city of Houston to achieve modern amenities, the city of Houston did not oblige. So, the early pioneers of Independence Heights said, “Well, what did they do to chart their own path, have their own water department, their own city, pave their own streets?” What they did was file for a city charter. So, that’s how they were able to start this African American city.

It was not their idea of starting the city where it was filled with Blacks. It just happened that way because Jim Crow and segregation were running rampant at the time. And what I know about my ancestors is they really wanted sovereignty. They wanted to be able to chart their own path, be in their own space where they were free from racial terror and all the other things that were happening at the time. Independence Heights afforded them that opportunity to do that.

DEFENDER: What year was it chartered as a city?

DEBOSE: 1915 is the year it was chartered as a city. Around November 1914 they started petitioning Harris County to apply and be able to get this charter started. In December they filed. Then on January 16, 1915 they actually held an election and they woke up on January 17 the independent city of Independence Heights. They voted in their first Black mayor, which was George Burgess. They had a commission-style government. They had already been building their own little town, so they just continued to work, but they had a little bit more power.

What people don’t realize, when it comes to land ownership, especially back in those days, and even now, is land ownership meant so much more than owning land. It meant that you could vote and you could hold office. What people don’t realize is that if you didn’t own anything, you didn’t have a right to vote. So, those were the things that were important, beyond just starting their own city. They wanted to be able to chart their own path.

DEFENDER: Why don’t more people don’t know the story of Independence Heights?

DEBOSE: I was 40 when I really realized the importance and significance of Independence Heights, and I’d grown up there all my life, going to church. My family, my mother grew up there. She was born in Independence Heights. My great grandfather Josh Powell came there in 1924. He came from the river bottoms of Ward, Texas. His grandfather had been enslaved in that area. He was from Kentucky, and so when he came to Harris County, the first place he lived was in River Oaks in a carriage house because he was a chauffeur. He saved his money, him and his wife, and they were able to purchase land in the city of Independence Heights.

What people don’t realize about the people who really populated that area, you had Exalton Delco Jr. He was the first Black zoologist that went to UT. His wife, Wilhelmina Delco, was one of the first Black state representatives in Texas, they all lived there. Their homes are still there in the community. We’re in the process of preserving them. Also, we had our own tailors, we had our own cab company. But you never saw it in history books. There were no documentaries made about it. It was not something mainstream America held as important.

DEFENDER: When did Independence Heights become part of Houston?

DEBOSE: Independence Heights was annex and became a part of the city of Houston after the 1927, 1928 stock market crash. The people of Independence Heights could not pay their notes to the Wright Land Company. The company then filed a lawsuit against the city of Independence Heights. At the same time, the city of Independence Heights had taken out a $100K loan or bond from the city of Houston.And they couldn’t pay because the people couldn’t pay any of their taxes and things. So, the city of Houston took this really vulnerable moment to open up what’s called a receivership.

Also, Houston was pressured to keep up with other major Texas cities that were expanding. Independence Heights became very easy prey because it pushed the city of Houston northward, and it couldn’t go west, south or east because of existing Houston neighborhoods. So, on Dec. 31, 1929, the people of Independent Heights went to bed as their own independent city. But on Jan. 1, 1930, they woke up part of the city of Houston. So, there went the first Black city in the state of Texas.

DEFENDER: What about the claims from other all-Black Texas communities?

DEBOSE: You have places like Kendleton, Prairie View, White Chapel. These are all early Black settlements that could have been towns, had they incorporated. The difference with Independence Heights and those places is that we incorporated.

DEFENDER: What’s the plan to share the story of Independence Heights?

DEBOSE: Locally, we’ve done exhibitions. The Conservancy is in charge of creating cultural programming. We are part of the newly established Emancipation Historic Trail. That allows us to be able to have a bigger voice if it is actually signed into law, where people can come into the community, they can get a walking trail map, go from house to house, learn who lived in these homes. We’re preserving homes. We are also preserving public buildings. We have eight historic churches that were founded a hundred and so years ago. We’re making sure those church histories, those archives are kept and preserved. That’s some of the things that we’re working on.

DEFENDER: What do you see regarding the future of Independence Heights?

DEBOSE: When I think about 20 years from now, what would I want to see in this community? I’d want to be able to know that the environment is still intact. Because there’s nothing like being able to come and visit in an authentic environment, as opposed to standing up on the side of the road and with a sign that says “Here was the first Black city in the state of Texas.”

DEFENDER: That’s huge. What other big things is the Conservancy working currently and in the future?

DEBOSE: The other thing that we’re working on is, we’re part of a national alliance of Historic Black towns and settlements. When we first learned about this, I never, in a million years, would’ve thought there were other Black towns because it just wasn’t something we were thinking about, because it was never in the history books. Now we know that Grambling, Louisiana was founded in the 1800s. Booker T. Washington sent his students there to help people get organized. Booker T. Washington came here to Dr. Covington’s house in Third Ward in 1911. Four years later, Independence Heights incorporates. And the McCullough family (one of Independence Heights’ founding families) was at that meeting.

Also, in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, Isaiah Montgomery and cousins Joshua P.T. Montgomery and Benjamin Green walked off the plantation and they headed to found their own town after the Jackson brothers got into a fight. They saw some mounds and between two bayous and that became their home, Mound Bayou. It was the jewel of the Delta. They had their own bank, their own bonds. And then Hopson City in Alabama. When they were drawing the boundaries for voting, Hopson City became its own city when whites in the area didn’t like the fact that Blacks were going to outnumber them in an election. So, they drew them out of it. And then Black people were like, “Okay, cool. We’re going to start our own town anyway here.”

And you had Tuskegee. Tuskegee was coming up. It’s not necessarily a Black town, but the Institute was there. And the town and the professors and the students grew up on that campus around it. And then of course, Eatonville, Florida, home of Zora Neale Hurston and Princeville, North Carolina, which was known as Freedom Hill. We’re part of that alliance. There were probably 20 Black towns in Kansas, Indiana, Maryland, Georgia. A lot of people think Allensworth is the only Black town in California. No, there were probably 20 more. So, the future for us is really connecting with those other towns because I think we make a better and a bigger voice when we connect together to tell our story as Black towns.

DEFENDER: Are there any other institutions you’re partnering with?

DEBOSE: We’re working with universities, particularly HBCUs, because if I had have known in college and studied that in history I would’ve known about these towns. We’re working with young people because we do need reinvestment in our communities. Those communities gave birth to us. They poured into us. What are we doing to give back to those communities as opposed to abandon in those communities? So, the future for what we are seeing ahead is to try to preserve what we have to try to make sure that our stories make it into journals, into history books, onto newspapers, fighting for these environmental justice issues that we’re seeing going on, that’s taking us over. That’s really what the future looks like for us, is to still be here if we can.

DEFENDER: What does the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council do?

DEBOSE: We are made up of eight councils, and those councils include most stakeholder groups in the community. We have a faith council. We have youth, seniors, our businesses, our schools, education and nonprofits. We have a Hispanic segment to us. And then we also have a group where we’re working on the history. We are a catalyst organization. What we do is administer community plans. We organize community to help develop these written plans as guides for the community. But we also will take the time to figure out who can we partner with to implement the things that are in those plans. Sometimes if it’s in our wheelhouse, we’ll do it ourselves. A lot of our work is really about preservation. I have people on my team that actually research history. We’re protecting homes, we’re landmarking buildings. We just started a Conservancy because after pandemic you have to think about what’s next. And it made everybody think differently about, we’re not going to be here forever. So, what are we going to do to preserve conserve what’s here? Our organization is really a catalyst to get work development and preservation and revitalization done in the community.

DEFENDER: What’s the racial makeup of Independence Heights now?

DEBOSE: Now? So, of course, Houston is changing. Texas is changing and so, our demographic makeup is changing. Our community is probably about 53% Hispanic. And then you have the next population of people being African Americans, with about 20% white. It’s really shifting. What we noticed probably about 20 years ago, because I started doing this work after Hurricane Katrina, we started to see Latinx families come into the community and start to buy. And the difference between that and what we see happening now is that those people were coming to homestead. They were coming because they wanted a place to live and be in a community.

What you see happening now is corporate giants coming in and buying masses of land and putting all this development up. And there are renting people who are moving into these new developments. I call them front-loaded garages or modern-day shotguns, townhouses. Those residents are there only for two years, at the most. And then they’re gone. So, you don’t have that “front-porch, I know Mrs. Jones, go around the corner and get me a cup of milk” type of environment anymore. Our city is turning into this baby New York, where neighbors don’t know each other. There’s no park you can walk to you. People pull up into their drive, into their garages. You never see them. So, it’s a hard shift from what I grew up in to see this kind of development happening in large part because we’re in the city with no zoning.

DEFENDER: For those who don’t know, exactly where is Independence Heights?

DEBOSE: Independence Heights is about two miles north, Northwest of city of Houston. We’re just west of I-45. Our northern boundary is Tidwell. And 610 is our southern boundary. Shepherd is our western boundary.

DEFENDER: What help can individuals and organizations give to the IHRC?

DEBOSE: So, we’re coming out of this pandemic and we’re having to rethink how we do business, like everybody else. A lot of what we had done prior to the pandemic, we were doing in-person senior programs and youth programs. The community has shifted. Things have changed. We’re still working in gardens because even though we have a Whole Foods over there, we still are a food desert, because the access to it and getting to these places is challenging. The Whole Food model is probably good for us, but we can’t afford it. So, we’re working in gardens. So, there’s opportunities to volunteer with us once a month with our gardens. Also, we’re doing oral histories. We meet on the fourth Saturday of every month with our Legacy Families program where we’re interviewing families and scanning their historical pictures and documents. This is all in preparation for the Emancipation Trail.

Also, as our organization is a catalyst organization, we are a 501 c3. So, we have financial campaigns that we run all the time. So, people can always donate. We do work on houses. When we had these disasters, we just had Winter Storm Uri. We had Harvey. And then we had Emelda in-between that. So, we’re still working with people to try to get their homes fixed. We depend on those organizations with resources to be able to come and help us restore and rebuild these homes that are in our community. So, corporate America, like Citgo gave us $6 million to restore 300 homes after Hurricane Harvey. And they put their staff on the ground and teams to help us be able to do that. So, those are ways that people can get involved. There’s always somebody’s house needs painting. There’s always somebody who needs an old shed torn down or someone who needs their home fixed. There’s a lot of ways to get involved.

OTHER HISTORIC INCORPORATED NATIONAL BLACK TOWNS

- Grambling, LA

- Mound Bayou, Mississippi

- Hopson City in Alabama

- Eatonville, Florida

- Princeville, North Carolina (aka Freedom Hill)

- Allensworth, CA

WAYS TO LEARN MORE ABOUT INDEPENDENCE HEIGHTS

HistoricIndependenceHeights.org

TANYA DEBOSE ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Twitter: @tanyadebose (Disruptive Historian)

Instagram: tanyadebose

Facebook: Tanya Debose

Words to Live By: “If you’re quiet about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you loved it.”